How to Achieve Work Life Balance

Published: Jan 18, 2021

Joanne was feeling overwhelmed by the volume of work and her inability to take time off to rest and replenish. She worked 10 hours every weekday and, on most Sundays, which left her with a limited amount of time to be with her young family. In addition, she had a seriously ill parent living in another state, placing greater demands on her energy sources which she felt were well and truly depleted.

When she came to executive coaching, her number one goal was to achieve work-life balance. She had been promoted 6 months prior to a new executive role reporting to the CEO of a biotech multinational company. She was a highly educated and accomplished STEMM* leader who had worked her way to the top of the organisation from a junior technical role.

However, she now found herself leading a significantly larger team spread across Asia Pacific. Not only was she dealing with several countries, nationalities, and languages, but the technical complexity of her work had also increased. She kept her scientific/technical knowledge up to date through company training and scientific journals however, extremely limited leadership development opportunities were provided.

After our first coaching session, we jointly discovered that she needed to bolster several essential leadership skills. As is often the case, most leaders transition to senior roles without much consideration to the “other” non-technical skills: the human skills. That is, until they begin experiencing excessively high and chronic levels of stress.

*STEMM stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths and Medicine

Sources and consequences of stress

We all experience situations, thoughts and emotions which can trigger stress (these are called stressors). Stressors can include being late for work, worrying about job security, experiencing conflict with a colleague, having an argument with a loved one, dealing with sickness, or having a huge workload.

Leaders often report that the most stressful thing about their job is not having enough time to complete everything they need to do. Another major source of stress are difficult interpersonal relationships, both at work and at home. A third source of stress is of a physical nature – sedentary jobs can leave us feeling tense, exhausted, and drained by the end of the day. There are stressors related to career and life stages, for instance being unhappy about progress.

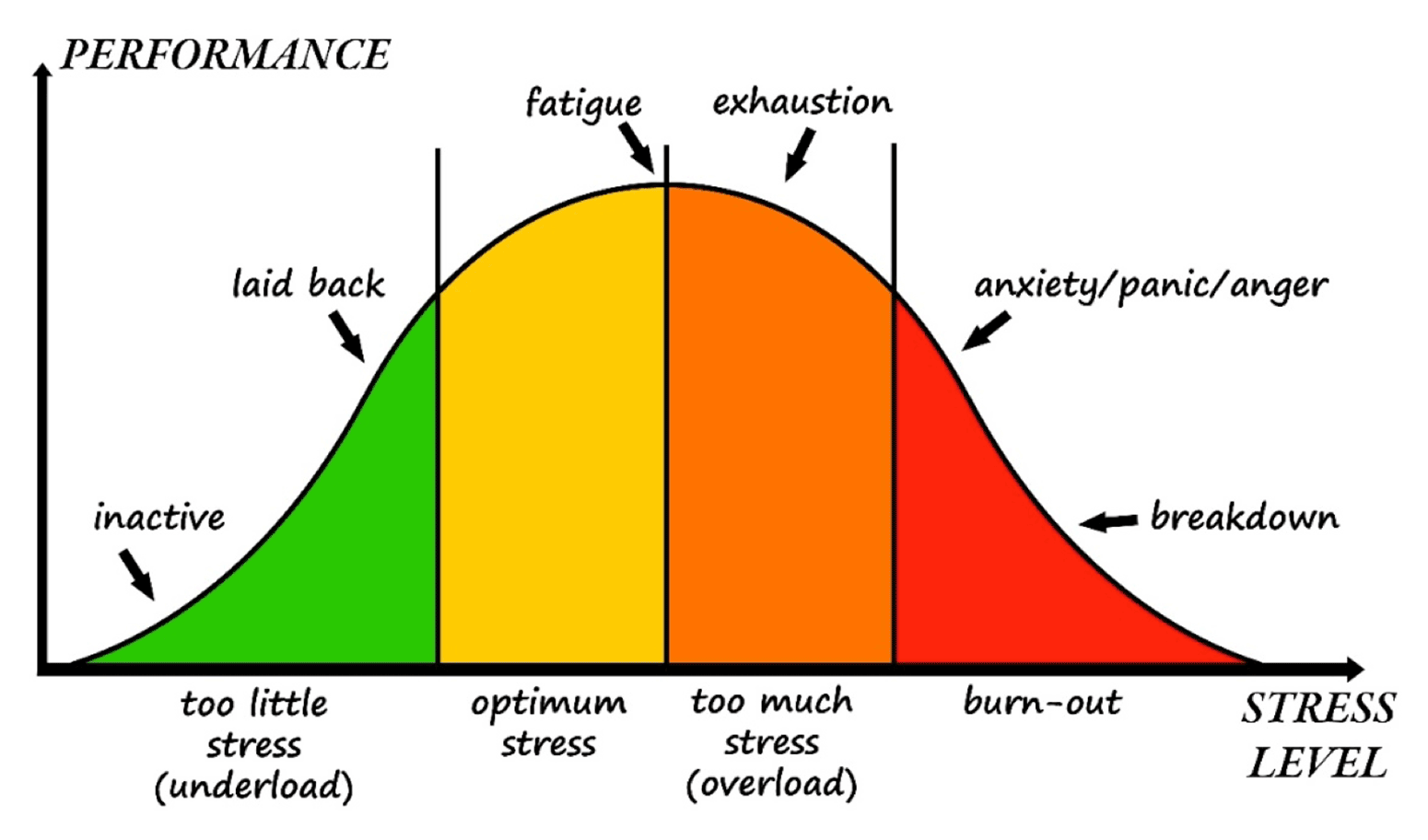

Undesirable stress occurs when we find the range of stressors in our lives excessively challenging or threatening. However, experiencing stressors is not always a bad thing. Indeed, when we are not feeling overwhelmed, stressors can be helpful as they prompt us to act with energy and purpose.

Figure 1. Relationship between performance and stress (Image: Adobe Stock)

Unrelieved stress can make us feel overwhelmed and out of control. Constant exposure can cause physical symptoms, aggravate many illnesses, and lead to anxiety and depression. Stress not only affects our bodies but can also affect the way we think, feel, and behave, potentially resulting in harmful actions to ourselves and others.

To better understand the effects of stress on organisational wellbeing and leadership refer to Chapter 9 – Nurturing Resilience and Wellbeing (at work), pages 143-160 in Scientists in Every Boardroom (Campbell, 2019).

Unfortunately, burnout has become commonplace in the workplace due to unmitigated sources of chronic stress. Employee burnout is escalating at an alarming rate globally, with an estimated $125-190 billion in related healthcare spending each year (WHO, 2019). In many cases, toxic leader-follower relationships lead to burnout. It therefore stands to reason that preventing burnout must be a compelling reason for organisations to provide leadership development/coaching to new and existing leaders moving up the organisational ladder. Leaders undergoing transitions require more sophisticated human skills.

Managing stress begins with self-knowledge

Our response to the stressors in our lives will depend upon a range of factors such as our resilience, whether we are already dealing with too many other stressors, and our ability to reframe (also known as cognitive restructuring), among others.

Understanding all the factors and adjusting the right ones can be quite complex. ONE SIZE DOES NOT FIT ALL. As such, executive coaching emerged as a critical learning & development (L&D) tool in helping leaders and their teams avoid burnout and indeed maintain health and wellbeing.

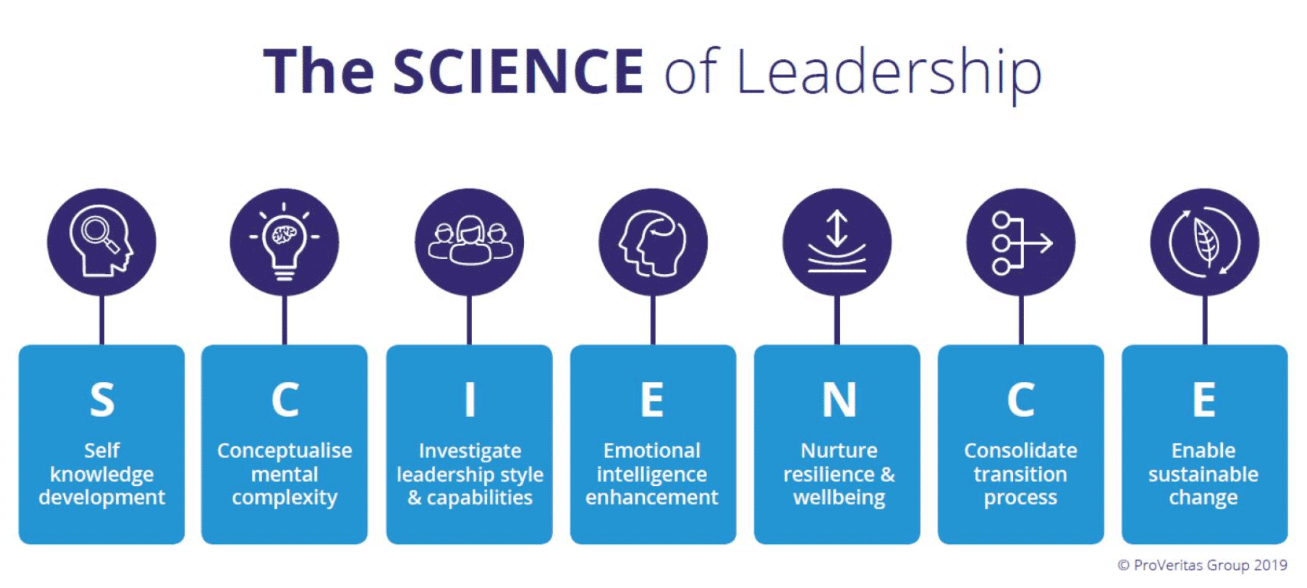

Understanding the sources of stress, and putting in place constructive actions to address them, is one of the hallmarks of high performing leaders. These are leaders who dedicate effort to developing deep self-knowledge (e.g., character strengths & values, personality strengths, and potential derailers) to adjust all aspects of their lives to maximise performance (see figure 2).

Figure 2. The SCIENCE OF Leadership Coaching Framework

As part of our self-discovery, we need to assess our levels of satisfaction in all area of our lives. These levels of satisfaction are typically related to the amount of time and energy expended in each area. The Wheel of Life is a useful tool used to assess and prompt leaders’ needs for change in specific areas of their lives.

For instance, on a scale of 1-10, how satisfied are you with the amount of time and energy currently spent on your career? A low rating implies a low level of satisfaction – perhaps working excessive number of a hours a week. A high rating suggests there is balance, the leader is fully engaged at work, etc. Senior leaders often report low satisfaction in two or more of these areas:

- Career - overworked, or not advancing, or not fulfilled/engaged, etc.

- Personal/professional growth - insufficient development to support career transitions such as promotions.

- Relationships Management - poor conflict resolution skills, unsophisticated communication skills, low assertiveness, low emotional intelligence, etc

- Health & Wellbeing - untailored wellbeing habits, insufficient sleep, poor diet, etc.

These are all interrelated and in fact generate a vicious cycle. For instance, a leader may be overworked because of outdated personal productivity skills stemming from insufficient professional growth opportunities (either by choice because they keep working long hours and claim not to have time, or by working for organisations that are not attuned to their employees’ wellbeing).

Perhaps the leader lacks necessary relationship/interpersonal skills to establish appropriate boundaries with stakeholders and push back when required, which in turn creates mounting angst and health problems. As the leader becomes more sluggish due to suboptimal health or simply a “foggy brain”, they put in longer hours at work…and so the vicious cycle continues.

There is light at end of the tunnel though…. we have more control of our environment, thoughts, emotions, and behaviours than we tend to believe. That is, we can adjust and optimise them according to our individual strengths, flaws and needs.

Whilst achieving optimal high performance is beyond the scope of this article (indeed, that is the crux of executive coaching, which takes time), we can begin with straight forward actions to help us “redistribute” our time and energy. Let us begin with modifying our behaviours.

Personal productivity skills

Time management tools were quite simple until recently - largely dependent on writing out a “to do list” and crossing off the tasks as they were completed. Organisationally, there were paper-based schedules created by management – employees completed tasks as assigned.

However, with the emergence of the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) workplace in the last few decades, those tools have proven to be highly ineffective. Leaders must now develop sophisticated personal productivity skills instead of focusing on effective time management.

Personal productivity means working in alignment with our values, needs, abilities, preferences, and purpose. Being aware and understanding how to enact our values enable us to be productive on our terms - values are the reference point for all your decisions.

Often described as our character, our values can be measured and indeed, cultivated. Values make our decision-making process more efficient and effective by quickly eliminating options that are not in alignment with them. They also end up being the tiebreaker when we face extremely tough decisions.

This brings us to one of the most difficult issues faced by leaders: how to prioritise tasks, or how to decide which task gets done first and how much effort is spent on it. In his memorable book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, author Stephen Covey why and how to prioritise based on certain principles and it is at the top of ProVeritas’ list of recommended books for all leaders.

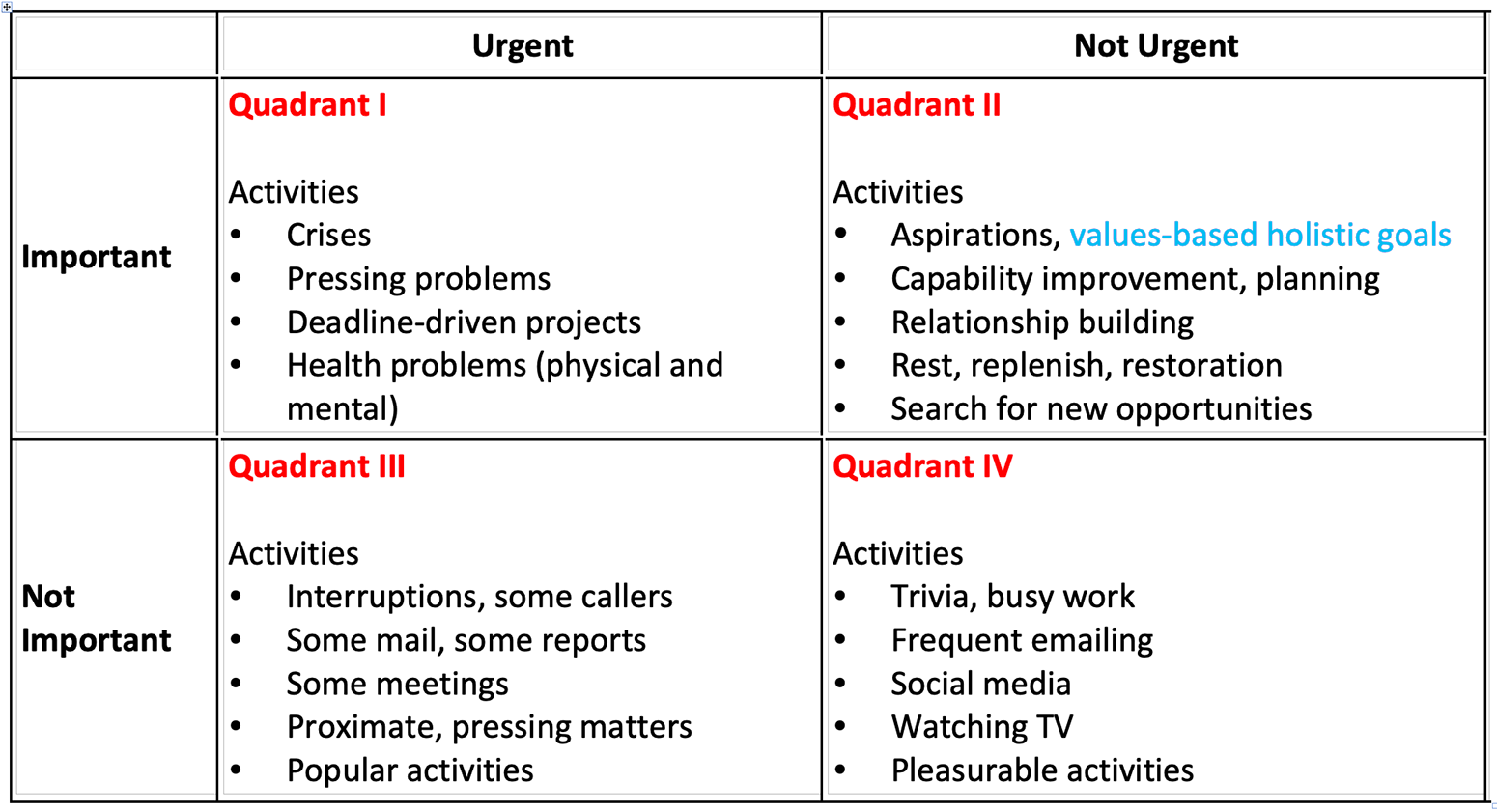

Covey developed a 2x2 time management matrix to assist us with:

- Clearly distinguishing between important and urgent activities

- Spending time on important matters, not just those that are urgent

- Focusing upon results rather than methods

- Having a reason not to feel guilty about saying ‘no

Figure 3. Covey Time Management Matrix - Activities

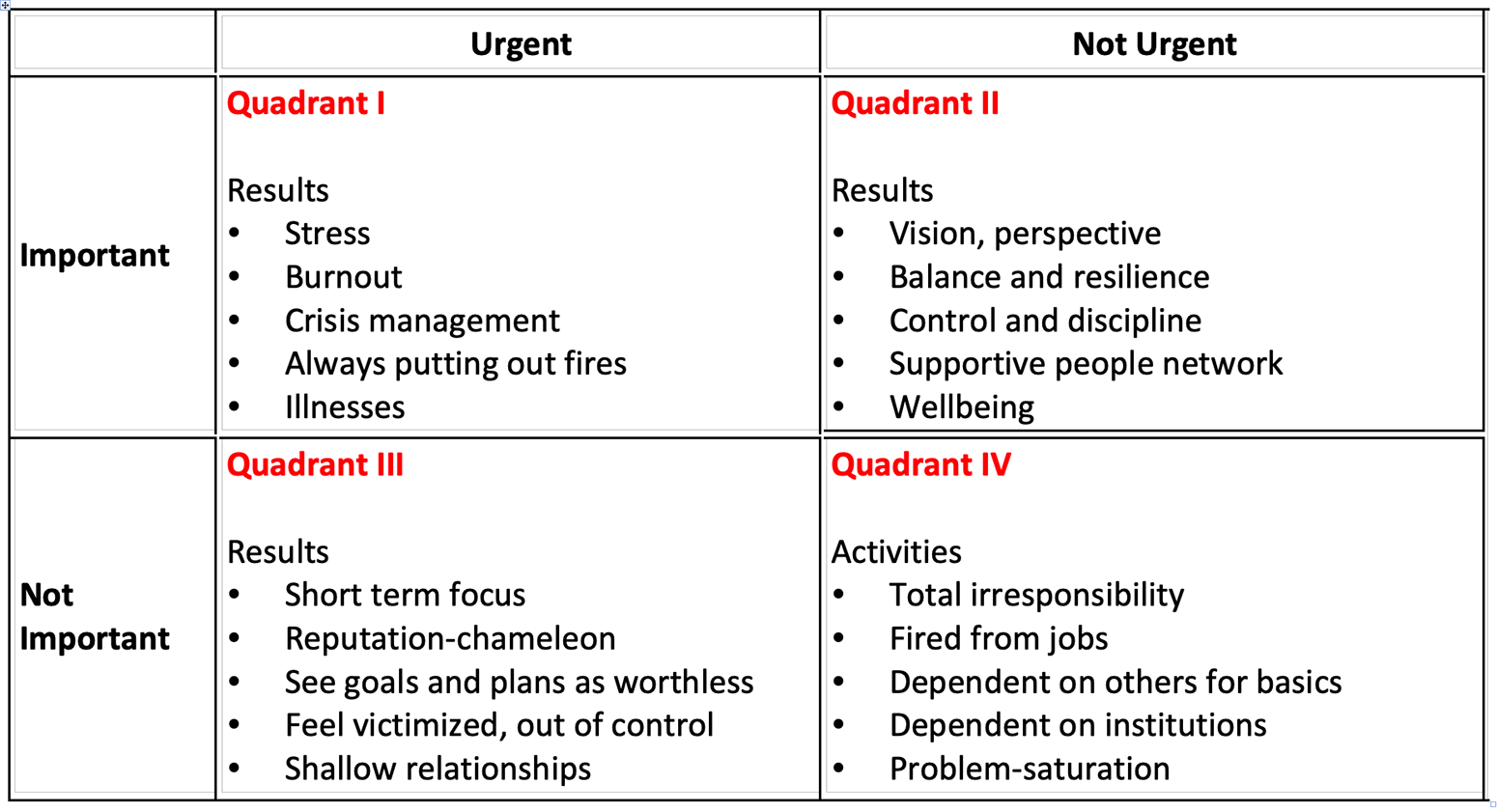

Figure 4 below shows the potential results obtained when focusing on Quadrants I, III and IV excessively. We should aim to spend more time and or energy on Quadrant II (shaded).

Figure 4. Covey Time Management Matrix - Results

Personal productivity skills recommendations

Central to efficient time management is identifying our tendencies to use time inefficiently. To do this, it is helpful to go through the list of time management recommendations below and determine which ones you need to implement or improve.

Recommendations for everyone:

- Read selectively. Unsubscribe from unimportant magazines and newsletters.

- Make a list of important tasks on a weekly, as well as a daily basis.

- Have a place for everything and keep everything in its place.

- Deal with your tasks in order of priority.

- Do one important task at a time.

- Make a list of a few 10-minute discretionary tasks – look for low hanging fruit.

- Divide up large projects into bite-size tasks to avoid feeling overwhelmed and falling into the procrastination trap.

- Determine the critical 20% of your tasks (Pareto’s law) which produce 80% of results. Focus on those tasks.

- Save your best time for important matters.

- Reserve some time daily when others cannot access you.

- Be aware of procrastination and ensure you spring into action (no matter how small) towards achieving important tasks.

- Keep track of time use and use apps, and smartphone alarms as reminders.

- Set deadlines and stick to them.

- Do something restorative while waiting – do breathing exercises at traffic lights or while on hold on the phone.

- Do busy work at one set time during the day.

- Reach closure on at least one thing every day, and give yourself a pat on the back i.e., bask in the achievement.

- Schedule personal time – this is part of the Wheel of Life exercise to illuminate areas needing attention such as time for mindfulness practise.

- Allow yourself to worry about an issue only at a specific time to avoid dwelling on it.

- Have long term goals – ensure your goals are holistic (all areas of life) and values based.

- Make continuous improvement part of your lifestyle, with self-compassion though.

Recommendations for leaders and managers:

- Set holistic and values based goals.

- Hold creative/innovative meetings early in the day when energy levels are highest.

- Hold routine meetings at the end of the day.

- Set a time limit for meetings.

- Cancel unnecessary meetings.

- Hold short meetings standing up (these may not require agendas and minutes)

- Have meeting agendas, stick to them and keep minutes and time.

- Start meetings on time.

- Prepare minutes promptly and follow up.

- Coach team members to find solutions for obstacles impeding progress.

- Avoid overscheduling the day and avoid scheduling back-to-back meetings.

- Use voicemail or have someone else answer phone calls when possible.

- Have a place to work uninterrupted (especially when working from home).

- Learn techniques for inbox management: first, set up a simple filing system to help manage your mail.

- You could use broad categories titled "Action Items," "Waiting," "Reference," and "Archives."

- If you can stay on top of your folders – particularly "Action" and "Waiting" folders – you could use them as an informal To-Do List for the day.

- Avoid touching emails more than once.

- Keep your workspace clean and uncluttered.

- Learn effective delegation skills. A rule of thumb for team leaders is to aim to reduce their workload by delegating about 70% of their work.

Final Remarks:

For leaders to manage stress successfully, they must always begin with developing self-knowledge (especially their values) to learn how to prioritise the myriad activities expected of them, especially when it is crunch time.

Focus on what is important, as guided by the Covey 2x2 matrix. At a more granular level, several time management recommendations can be followed to assist in the creation of habits that lead to overall positive results i.e., organisationally, and individually. There are other means of managing stress successfully, such as learning conflict resolution skills, practising journaling, and meditation (ProVeritas Group, we practise mindfulness instead of meditation), reframing or cognitive restructuring, among others. These will be discussed in future articles.

After exploring her values, strengths, and blind spots, and carefully reviewing her organisational goals and KPIs, Joanne began implementing applicable time management recommendations to operate within Quadrant II (Not urgent & Important) as much as possible. She immediately felt a sense of relief and greater control of her time.

Next steps for Joanne will be to cascade down these techniques to her whole team, and to engage in conversations with her peers and other key stakeholders to achieve support. For this, she will likely need to keep improving her communication skills (e.g., conflict resolution and assertiveness skills), and emotional intelligence capabilities. Just as important will be her nurture her emotional agility, resilience, and mental strength.

As a highly creative and conscientious scientist, Joanne is well placed to achieve and maintain work-life balance as she continues to build on and acquire new leadership capabilities during her coaching journey and beyond.

About the Author:

Recent Articles

- Elevating Science-Based Leadership in Every Boardroom Oct-24-2022

- Narrative Coaching for Planetary Health Oct-03-2022

- Emotional Intelligence: The Key to Exceptional Leadership Jan-31-2022

- A Year in the Life of a Leadership Coach Dec-15-2021

- How to Develop Self-Knowledge and Why it Matters Aug-23-2021